- Topic

39k Popularity

20k Popularity

48k Popularity

17k Popularity

44k Popularity

19k Popularity

7k Popularity

4k Popularity

115k Popularity

29k Popularity

- Pin

- 🎊 ETH Deposit & Trading Carnival Kicks Off!

Join the Trading Volume & Net Deposit Leaderboards to win from a 20 ETH prize pool

🚀 Climb the ranks and claim your ETH reward: https://www.gate.com/campaigns/site/200

💥 Tiered Prize Pool – Higher total volume unlocks bigger rewards

Learn more: https://www.gate.com/announcements/article/46166

- 📢 ETH Heading for $4800? Have Your Say! Show Off on Gate Square & Win 0.1 ETH!

The next bull market prophet could be you! Want your insights to hit the Square trending list and earn ETH rewards? Now’s your chance!

💰 0.1 ETH to be shared between 5 top Square posts + 5 top X (Twitter) posts by views!

🎮 How to Join – Zero Barriers, ETH Up for Grabs!

1.Join the Hot Topic Debate!

Post in Gate Square or under ETH chart with #ETH Hits 4800# and #ETH# . Share your thoughts on:

Can ETH break $4800?

Why are you bullish on ETH?

What's your ETH holding strategy?

Will ETH lead the next bull run?

Or any o

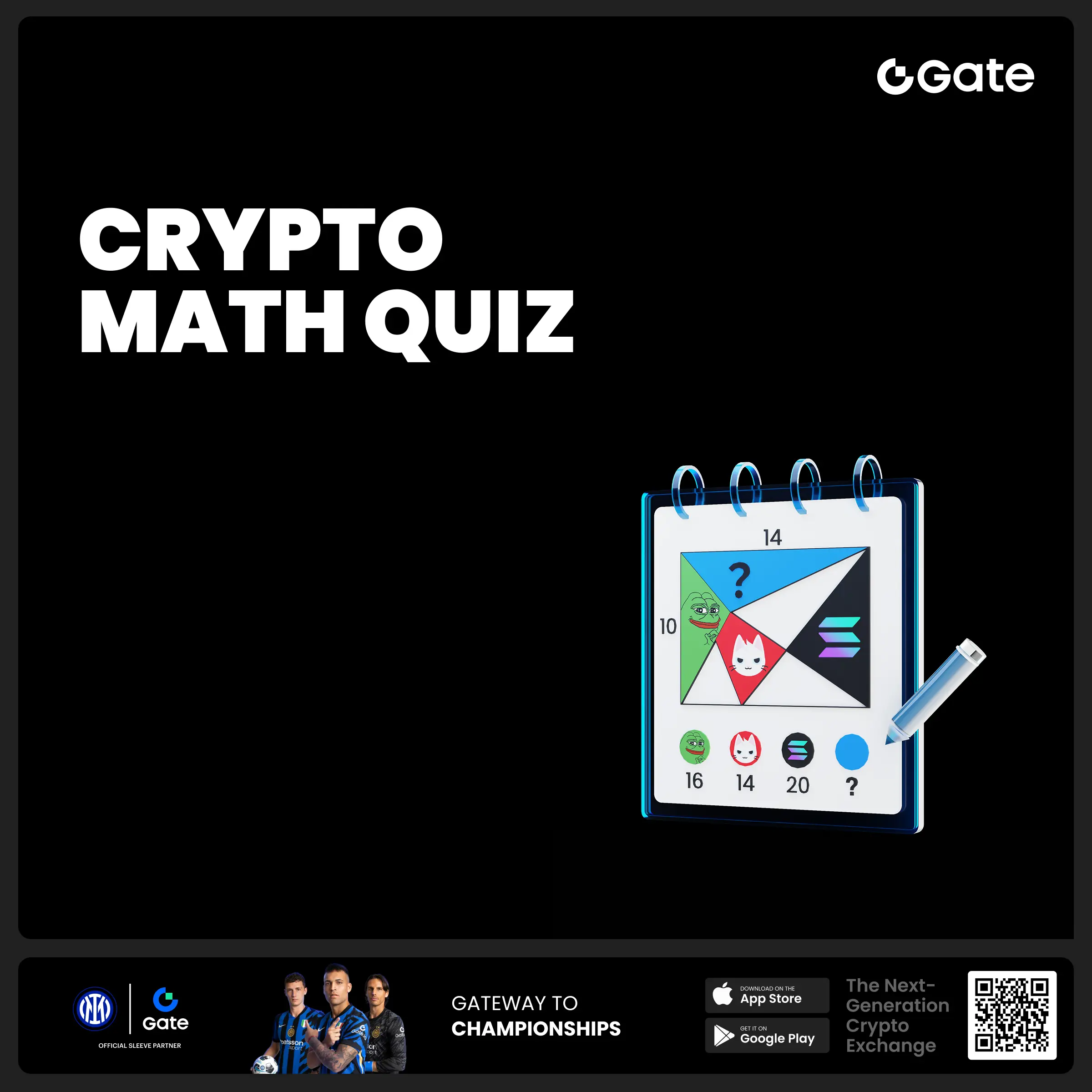

- 🧠 #GateGiveaway# - Crypto Math Challenge!

💰 $10 Futures Voucher * 4 winners

To join:

1️⃣ Follow Gate_Square

2️⃣ Like this post

3️⃣ Drop your answer in the comments

📅 Ends at 4:00 AM July 22 (UTC)

- 🎉 #Gate Alpha 3rd Points Carnival & ES Launchpool# Joint Promotion Task is Now Live!

Total Prize Pool: 1,250 $ES

This campaign aims to promote the Eclipse ($ES) Launchpool and Alpha Phase 11: $ES Special Event.

📄 For details, please refer to:

Launchpool Announcement: https://www.gate.com/zh/announcements/article/46134

Alpha Phase 11 Announcement: https://www.gate.com/zh/announcements/article/46137

🧩 [Task Details]

Create content around the Launchpool and Alpha Phase 11 campaign and include a screenshot of your participation.

📸 [How to Participate]

1️⃣ Post with the hashtag #Gate Alpha 3rd - 🚨 Gate Alpha Ambassador Recruitment is Now Open!

📣 We’re looking for passionate Web3 creators and community promoters

🚀 Join us as a Gate Alpha Ambassador to help build our brand and promote high-potential early-stage on-chain assets

🎁 Earn up to 100U per task

💰 Top contributors can earn up to 1000U per month

🛠 Flexible collaboration with full support

Apply now 👉 https://www.gate.com/questionnaire/6888

Zhu Rongji's son Zhu Yunlai talks about stablecoin

Source: Sina Finance

The China Europe International Business School held the fifth "Zhi Hui Zhong Ou · Beijing Forum" in Beijing on July 10, where Zhu Yunlai, former president and CEO of China International Capital Corporation and visiting professor of management practice at Tsinghua University, delivered the keynote speech. Below is the transcript of the speech.

Zhu Yunlai's Latest Speech

Thank you to the China Europe International Business School for inviting me to attend this discussion. When communicating with Secretary Ma Lei, it was mentioned that "China-Europe" cannot lose either character, which is a long-standing necessity. The current geopolitical situation is increasingly complex, but the friendship between the Chinese and European people must endure. The China Europe International Business School has also been active at the forefront of education and economic development since the reform and opening up.

The school has raised the topic under the current situation: what strategies should enterprises adopt under the restructuring of the global economic and trade pattern? I am fortunate to participate in this discussion and present some perspectives. Let's consider the factors that should be taken into account from a macro and long-term perspective, in order to systematically understand the possibilities of future development directions.

First, let's examine the context of world development from a historical perspective.

It has been 80 years since the end of World War II in 1945. Looking back, it has been over 110 years since the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Through this long period, the overall trend of global development is clear: the blue line in the chart represents output value, while the red line represents population. We can see that the global population continues to grow, while the speed of economic and production development has been even more rapid, especially in recent decades. However, at the same time, energy consumption has been rising continuously, and the emissions issue has become increasingly prominent—currently, the annual carbon dioxide emissions globally are close to 40 billion tons, which is a reality we must face. A noteworthy dimension is the change in energy efficiency: although the energy consumption per unit of output value has achieved systematic decline, per capita energy consumption continues to grow. This is determined by the fundamental model of global development.

Historically, the global population has an annual growth rate of about 5%, while the nominal GDP grows at an average of 7% per year; if we exclude the inflation factor of 3%-4%, the real growth rate of the实体 economy is approximately 3% per year. These data not only reveal long-term trends but are also key development variables for our current stage.

Climate Change

Another issue that needs to be recognized is climate change, which I have actually hinted at previously.

Records related to climate change can be traced back to 1850. To make it easier for everyone to establish a temporal connection, let's refer to this point: In 1851, the first World Industrial Exhibition was held in London, marking the beginning of the modern industrial era, not far from the starting point of climate records.

From the data, the red curve at the top represents the total carbon dioxide emissions per year, while the blue curve indicates the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (measured in PPM). In the early records, the carbon dioxide concentration was about 285 PPM, and it has now exceeded 400 PPM, representing a 50% increase from the initial level. The direct consequence of this increase is global warming — as shown by the orange curve in the third chart, which indicates the change in global average temperature, almost perfectly in sync with the rising trend of carbon dioxide concentration.

The scientific community has reached a clear conclusion: if the global carbon dioxide concentration doubles compared to pre-industrial levels, the global average temperature will rise by 3℃. The current concentration has increased by 50%, which is exactly half of the "doubling", and the actual temperature has also risen by about 1.5℃, which highly corresponds with the theoretical prediction. The World Meteorological Organization has pointed out that if carbon dioxide emissions are not reduced, the global average temperature may rise by 3℃ by 2030, which would be a doubling from the current level; in other words, the past increase of 1.5℃ due to a 50% rise in concentration would mean that if emissions are left unchecked, there will be an additional increase of 1.5℃ in the future.

This change is fundamentally different from historical climate fluctuations. Although the Earth has experienced alternating ice ages and warm periods, with temperature fluctuations exceeding 1.5°C or 3°C, those changes were driven by natural factors—such as periodic deviations in the Earth's orbital path, leading to cold and warm alternations typically on a millennial scale. In contrast, the current climate warming has entirely different driving factors and consequences: if the sources of human emissions are not eliminated, the trend of rising temperatures will be difficult to reverse and lacks the possibility of natural recovery.

If we develop the economy hoping to live better, in the face of such climate issues, if we do not solve them, this Earth may become an unsuitable place for survival, leaving us without a home, which is a problem that cannot be ignored; however, historically, the European Union has been an active participant in promoting climate governance and reducing carbon emissions. Unfortunately, perhaps due to sluggish economic development, the current attitude has become a bit vague. Climate issues should still be a key aspect that requires cooperation between our two sides and indeed among countries globally.

Next, let's take a look at the evolution of the global economic and trade landscape.

In terms of the total global trade volume (the sum of exports and imports), this figure has now reached 49.2 trillion USD, with exports and imports roughly accounting for half each. The statistical approach of adding imports and exports is taken because, for the countries participating in trade, both exports and imports are important components of their economic activities, which can more comprehensively reflect the level of interaction in the global economy. Looking back from the 1960s to the present (data from this period is relatively easy to obtain), the scale of global trade has achieved substantial growth; if we look at the proportion of total trade to the world's economic output, it has increased from around 20% at that time to nearly 50% today, indicating that trade has always developed in tandem with the global economy.

However, after 2000, global trade experienced a period of rapid growth until the 2008 global economic crisis, after which the momentum of trade and output expansion seemed to encounter a bottleneck. The causes of this change are worth discussing, even as we focus on future discussions.

From the perspective of the regional composition of global trade, if we divide it into regions such as Africa, Asia (including China, meaning the total of China and other regions in Asia forms a complete Asian bloc), North America (including the United States), and Europe, observing the economic changes over the past 30 years may provide clues for future development. This data not only presents the current pattern but also implies the process of its formation—the core value lies in helping us distill the basic characteristics and further consider the actions that can be taken.

In relative terms, Europe still holds a significant share in global trade; although China's trade scale is already quite impressive, there are still differences compared to Europe; at the same time, the trade volume of other regions in Asia is about twice that of China. Clarifying these numerical ratios will provide important references for our subsequent analysis.

From the perspective of net trade, countries above the zero axis are net exporters (trade surplus), while those below are net importers (trade deficit). Data shows that since the 1990s, the trade patterns of Europe, Asia, and the United States have changed significantly over time, with China's surplus scale exhibiting systematic growth. As of the latest statistical year, China's trade surplus reached $1 trillion, while the United States' trade deficit stood at $1.3 trillion, resulting in a difference of $0.3 trillion—this figure happens to correspond exactly with the global overall trade deficit. This indicates that if we exclude the trade balances of China and the United States, trade in other regions of the world is essentially in a state of balance. The causes of this structural characteristic warrant in-depth exploration: the issue of the United States' trade deficit has persisted for a long time; despite repeated trade frictions and ongoing discussions, the scale of the deficit continues to expand.

Regarding the issue of the trade balance in the United States, my initial analysis is as follows: the United States has maintained a long-term surplus in service trade, which is a net export status, while its overseas investment income (such as dividends, interest, etc.) also forms a surplus—these two items should, to some extent, offset the deficit in goods trade from the perspective of international balance of payments. However, the actual situation is that their scale is far from sufficient to cover the gap in goods trade. Later, I noticed a set of data that is more worthy of attention: the balance of new debt added in the United States continues to expand each year, which directly reflects the overall level of liabilities represented by federal government debt is systematically rising. Although the fluctuations in the scale of debt may be influenced by multiple factors, the baseline of new debt (i.e., the minimum annual increment) has been continuously increasing, and this trend is far more significant than short-term fluctuations.

We can't help but wonder: Why can the US debt continue to increase? This may be closely related to its representative system of congressmen— the controversies surrounding the debt ceiling are essentially discussions about whether to meet the ever-growing payment demands, which are driven by the maintenance of their respective constituents' interests. Although this clue is not enough to fully explain the root causes of the debt increase, it at least reveals a phenomenon: a significant portion of the federal government's borrowing is used for public procurement (including transfer payments to residents), which may be pushing the debt level ever higher.

The demand behind this debt growth may also reflect the balance of interests among different groups within the U.S. economic structure. At the same time, since the reform and opening up, China has continuously upgraded its industry and manufacturing capabilities through an export-oriented strategy, gradually becoming an important supplier in the global supply chain, while the U.S. has actually been playing the role of the demand side, only shifting in the choice of suppliers based on the principle of selecting the best value for money. From an economic logic standpoint, this choice reflects trust in supply capabilities, while conversely, producers selling to the U.S. indicates trust in their payment capabilities—if the U.S. lacked payment ability, there would not be a sustained input of goods. This supply-demand relationship also reflects the interdependence in geopolitical economics.

From the long-term historical trajectory of U.S. import tariffs, the changes from 1890 to the present are quite revealing: from 1890 to the late 1980s, the level of U.S. tariffs exhibited a systematic downward trend, which coincided with robust economic growth and marked a significant developmental phase. In the early stages of China's reform and opening up, the relatively low tariff barriers in the U.S. effectively opened its import market to the world, providing opportunities for capable suppliers, including China, to drive economic growth through exports.

However, the current tariff policy shows a significant reversal, as if it has overnight returned to the protectionist model of sixty or seventy years ago, or even earlier. Can this policy shift really bring the expected benefits? In fact, the essence of trade is voluntary exchange, not coercion. To think that merely raising tariffs can attract manufacturing back to the country completely ignores the difficulties of rebuilding complex supply chains in the short term, and it is also questionable whether market entities have enough willingness to respond.

In contrast, the actual effect of this tariff policy is more like a continuation of the "America First" tax reduction policy—rather than achieving goals such as industrial repatriation, it serves more to benefit specific policy logic and interest groups.

The demand for the expansion of the U.S. debt scale has always existed, while tax reduction policies inherently contradict this demand—although tax cuts align with the interests of business owners, the rigid pressure of public spending has not diminished as a result. Against this backdrop, increasing tariffs appears more like a substitution for policy funding sources: hoping to shift the social responsibilities that domestic enterprises should bear onto foreign importers, thereby "reducing the burden" on local businesses.

The signal this policy sends to voters is "the costs will be borne by foreigners," but the reality is clearly not so: the ultimate bearers of tariffs are in fact American consumers. Once tariffs are raised, the prices of imported goods are likely to rise, and American consumers will pay the price. What’s more concerning is that domestic American companies may also take this opportunity to raise prices; since they can maintain profits without the need for technological innovation or efficiency improvements, there is naturally a lack of motivation for companies to improve, and ultimately all costs will still be passed on to consumers. As for whether consumers can see through the benefit chain behind this policy, it will likely take time to provide an answer.

This chart shows the comparison of the stock and yield of U.S. overseas assets from 1976 to 2024 with the stock and yield of foreign investments in the U.S. The data indicates that U.S. foreign investments have consistently maintained a high return rate of 5%-10% over the long term, which aligns with the global competitiveness of U.S. investment institutions—its extensive global layout and strength indeed support its ability to engage in more complex or higher-risk investments, thereby achieving higher levels of return. In contrast, the return rate of foreign investments in the U.S. is slightly lower, but the fluctuation trends of the two are highly consistent: around the 1980s, the average return rate for both types of investments was about 8%-9%, while today there is a systematic decline. This global phenomenon of decreasing investment returns may have offered us a glimpse into future trends and reflects a systematic historical trajectory. It is worth pondering whether this decline is related to overly aggressive growth policies. As the scale of policy stimulation continues to expand, the marginal efficiency inevitably declines, which may be one of the significant reasons for the decrease in return rates.

Let's talk about the currency issue again.

In conjunction with the growth trends of major global economies mentioned earlier, China's industry has undergone nearly half a century of systematic development, and in the monetary field, it should have more opportunities. From the perspective of trade practice, one of the core functions of money is as a medium of exchange—it can be paper currency, metal currency, or specific currencies like the US dollar or Chinese yuan. Essentially, it serves as an intermediary in the transaction process: selling goods to receive money, and then using that money to purchase consumer goods or production materials, completing the closed loop of value exchange.

From the current distribution of currencies in global foreign exchange reserves, the US dollar accounts for about 50%, while currencies such as the euro, pound, and yen show a "one large, many small" tiered characteristic, meaning that aside from the euro, the remaining currencies generally account for less than 10%. This pattern raises questions: from a global trade perspective, where will the future settlement currency system head? More importantly, in recent years, currencies have gradually become tools of geopolitical strategy—any country's currency is deeply tied to its domestic economic policies, and the spillover effects of these policies can be transmitted globally through currency transactions: when you use a certain country's currency for cross-border transactions, fluctuations in its domestic policies may directly affect your interests.

Especially during the current U.S. government period, the uncertainty of policies has significantly increased, and it cannot be ruled out that it has deliberately amplified the volatility of system expectations. The essence of currency is the credit system, "national credit is the core of modern fiat currency," which relies on certainty—if the value of currency fluctuates unpredictably, trading entities find it difficult to plan, which contradicts the credit logic of trade. For example, in the early days of reform and opening up, the Japanese yen experienced severe fluctuations (rapid appreciation followed by quick depreciation), causing many production and trade enterprises to suffer significant losses. This also illustrates that "currency value stability" has become a systematic demand for the normal conduct of trade. In this context, has the rise of stablecoins come into being? For trade practitioners, the core demand for currency is stability—avoiding the risk of "receiving dollars today and having them depreciate significantly tomorrow." Of course, Mr. Wang is an expert in this field; I approach it more from the perspective of trade practice: no matter how the form of currency evolves, as long as it can maintain currency value stability and reduce the uncertainty brought by fluctuations, it is a choice that meets trade demands.

From a financial perspective, what I understand about stablecoins is that they should be distinct from cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, and also different from traditional fiat currencies. Essentially, it is an innovatively designed token, with its core logic being to incorporate various factors that influence the coin's value into a framework similar to an "investment portfolio" through a systematic and legally compliant financial market management approach, allowing for proactive and systematic regulation.

The core goals of stablecoins have two points: first, to maintain value stability, and second, to ensure transaction efficiency—such as achieving fast settlement. This stands in stark contrast to traditional trading models: in the past, reliance on banking systems, letters of credit (LC), or interbank transfers often resulted in many frictions due to cross-regional, cross-national, and cross-institutional processes, whereas the design of stablecoins is intended to break through these limitations.

In the context of the current new era, the market's demand for efficient and stable trading mediums is increasingly prominent, and the technological ideas of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin have also provided inspiration—people are gradually realizing that through a modular token management model, it may be possible to construct a better payment tool. Specifically, it requires a professional financial team to systematically incorporate variables such as price volatility into the management system, ultimately providing a form of currency that is efficient, low-volatility, and highly secure. This idea resonates with Hayek's monetary theory: currency need not be exclusive to the state; private entities may also participate in supply, and the key lies in how to establish and maintain the credibility of currency value.

However, there is still a considerable distance between stablecoins in the current context and "private currencies." A more realistic path may be for larger, more transparent international institutions to issue them, with their operating algorithms needing to be publicly accessible—this is in stark contrast to the anonymity of Bitcoin. Stablecoins need to establish credibility through "naming," including clear disclosure of settlement mechanisms, collateral asset composition, or specific currency value management methods. Ultimately, the value of stablecoins must be validated by their actual application results: if they can continuously maintain stability and efficiency, they may gradually become a part of the global consensus trading foundation through the market effect of "good money driving out bad."

Development Opportunities

Below, I have organized population and output data by region, hoping to use this as a benchmark to explore potential development opportunities.

For example, Africa's population has grown from 500 million in the past to 1.5 billion, becoming a highly potential market. Taking the photovoltaic industry as an example, Africa originally lacked stable power supply, while the combination of solar panels and batteries can quickly provide a stable power source, with electricity prices only half that of traditional coal power, and achieving zero emissions, which perfectly meets the global demand for "protecting the Earth home." In this field, China not only has rich and competitive products but also reserves of system engineers and technical workers—facing such a large population base in Africa, we undoubtedly have vast market potential.

Despite potential bottlenecks in global trade, business opportunities still exist. If the current U.S. government's policies force a restructuring of global supply chains, China, with its strong production capacity, transportation network, and human resources (hundreds of millions of workers and engineers), is still expected to gain an advantage in the restructuring— the key lies in how to systematically leverage these advantages. It is worth noting that the logic of exploring markets is similar to shopping: consumers enjoy discovering new products but are put off by overly aggressive salespeople. Similarly, when promoting products in the global market, it is necessary to avoid being overly eager for quick results and focus on building long-term trust.

From the historical trajectory and current situation of the new energy industry, the growth potential of its market scale is clearly visible. The "green going abroad" sector has shown a positive trend: the price of photovoltaic components continues to decline, and export volumes are steadily rising; products like electric vehicles also directly address global development pain points, driving green transformation while being cheaper to meet travel needs, representing a rare opportunity. In fact, the costs of these industries have decreased by 70%-80% over the past decade, and this cost advantage has laid a solid foundation for further market expansion.

From the perspective of the distribution of global per capita output and innovation index, China's ranking has changed significantly from 2016 to 2023: efforts in the field of innovation have enabled it to progress far beyond most developing countries, and per capita output has also continued to improve. These achievements not only provide a solid foundation for future development but also establish confidence in overcoming various difficulties.

From the perspective of global economic stratification, there is a significant disparity in per capita output among high, middle, and low-income countries, and the industrial structure of different types of economies also has its own focus. Currently, China is at a critical stage of transitioning from a middle-income country to a high-income country. Even though the threshold for crossing over is relatively no longer insurmountable, the core of development still lies in achieving transformation through industry innovation and systematic enhancement, realizing high-quality development, while also resolving the historically accumulated overcapacity.

In the face of profound changes in the global landscape, the ideal path may still be to expand development space on the world stage—of course, this requires more mature negotiation strategies and communication wisdom. As emphasized by the "dual circulation" strategy: internally, it is necessary to digest internal issues through industrial upgrading and quality improvement, while externally, we need to play the "international card" to release systemic external spillover development potential. China's advantageous products have practical value for improving people's livelihoods and raising the economic level in developing countries. If more countries can recognize this mutual benefit, we can achieve a win-win situation in cooperation, and China's economy can also move towards a new stage of development through mutual benefit.